In this class, we follow the practices of agile project management, meaning that we make adjustments along the way, and will adjust the class to meet the needs of the people in it.

Agile projects are managed in short bursts. Development used to be in very long cycles, but now it’s in short phases – three, four weeks. You can’t get a lot of work done, but you’re always able to ship something.

In an agile workflow, the whole t3eam gets together every morning and does a “stand up.” We’re going to do the same thing, focusing on three questions:

- What have you accomplished since the last class session?

- What are you going to accomplish today? (The one thing you most want to get done.)

- What are you blocks? (What’s in the way of your One Thing You Most Want to Get Done?)

We wil apply Git to our own pages, then use a magic carpet called gh-pages to make our sites instantly public. “One-click deploy” - Automations. Going to code in public.s

#####Resources:

- Cheatsheet for Git: http://www.git-tower.com/blog/git-cheat-sheet/

- Basic Git training at https://training.github.com/.

- For a deep, advanced view of Git, there’s an eBook called Pro Git: GitSCM

tryGit is highly recommended as a starting point: it’s a web-browser based series of tutorials and exercises.

#####THINGS NOT TO DO:

- Don’t put spaces in folder names.

- Never go into the .git file.

- And above all, NEVER PUT A REPO INSIDE A REPO!

cd takes you to your home directory, and if it does, it’s possible to accidentally make a repo. So always know where you are in the file structure. To see if you’re in a repository, you can use ls -al and make sure that there’s no .git file, or you can use the command git status. (More on that one shortly.) You can also use the command pwd (print working directory) to show what directory you’re in at the moment.

#####What’s Happening in Git

It is possible to use Git witha UI, but most developers use the command line.

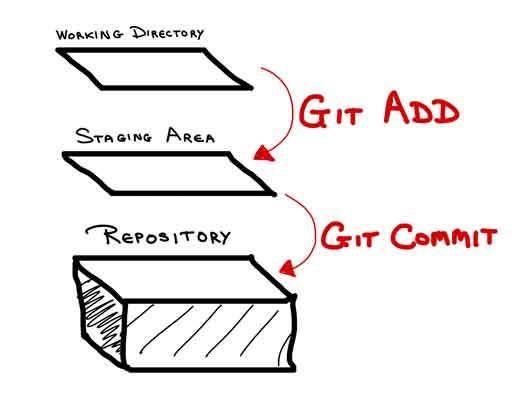

It can help to create a mental picture of what’s happening when you’re using git. One PCS student/TA used the image of a schoolbus. You can devise your own. This is one possible visual metaphor:

Think of folders and files as being stuck on clear piece of mylar. All active work is being done in the working directory.

When the current state of the work has reached a place where you want to save a version, then all the changes are moved into a staging area.

Those changes can then be committed, or permanently recorded, into the repository for that project.

Git uses arcane language. The most important commands are:

- git status - Lets you see the current state of all the files in the project, and what has or hasn’t been committed. This is the git command you’ll use 10x more than any other; it’s the git equivalent of pwd or ls and enables one to have situational awareness.

- git add - Moves the latest changes into the staging area, from where they can be committed.

- git commit -m”Why you’re making this commit“ - Commits the changes that were in the staging area, puts them into the repository and takes a snapshot of the repo at that moment. Always leave a message: it’s for other designers and developers (including your future self). (If you forget the -m, you’ll find yourself in the VIM editor, which is the system telling you, “You WILL leave a message! Here’s my ancient word processor to help you do it.” To get out of VIM, type :q or Shift + ZZ or even **Esc + Shift + ZZ)

- git help - Shows the most common commands.

- git history - Show history.

- git log - Shows everything you’ve done.

- git mv - Moves something from one place in a tree to another.

- git diff Shows changes, but there are more useful ways to do this.

To configure settings:

- *git config –global user.email *email@whatever.com **

- *git config –global user.name *Your Name **

- git config –global -l - To show the configuration

All git commands are git something, because they’re all subcommands of git.

The developer’s cycle is:

- Edit.

- Stage. git add

- Commit. git commit

- Repeat.

Generally, you want to add files one at a time: * git add index.html * git add main.css * Etc.

However, it is possible to add all changes to the working directory at once with the command git add -A. (The “A” has to be capitalized.) This can save time, but it cah also cause heartache. (There are similar commands git add . and git add -u, and there’s an article explaining the differences between them all here.)

Once a file has been added to the staging area, it can still be removed, with the command git rm – cached Name-of-file.

Here’s a very handy command-line shortcut: Control + C will stop whatever task is currently running. (In notes, I starred it and called it, “The Best Command-Line Shortcut Ever,” but I don’t remember what crisis it saved me from at the time.)

When you enter git commands (especially git status), read everything that git says in the Terminal, even if it makes no sense. Look to make sure that you don’t see the words “error” or “warning.” Gradually, it will all start to become clear, but that breakthrough won’t happen if you’re not reading it along.

(This whole Git/GitHub process is the most difficult part of the course. But this is how professionals work.)

Your entire repo, with all its versions of your project, can be cloned and kept online, on GitHub. It’s like a magic mirror, and versions of the project can be pushed and pulled between the two. The version on your computer is the “local” version; the one on GitHub is the “remote” version.

Every GitHub repository has its own URL. Files can be moved between the GitHub repo and your computer via either HTTPS or SSH protocols. (There’s an article on the two options here. GitHub recommends HTTPS over SSH.)

A git repository can be intialized on a local computer, then pushed to GitHub, or it can be started on GitHub and cloned to the local computer. The repo names on GitHub and on the local drive have to match.

Here’s how it works if you start locally:

- Open the Terminal app.

- Change to the directory that is CONTAINS your new directory.

- Use the ls command to see the contents of the current directory and make sure that it contains your directory.

- Change directory into your folder using the cd command: cd YourNewRepo

- Use the command git status and make sure that there’s an error message. (This shouldn’t be a git repository yet, so git status will produce an error. If it doesn’t, then this is already a repo – stop now!)

- (Assuming that the previous step did indeed yield an error message) Turn the folder into a git “repository” with the command git init.

- Use the command git status to make sure the initialization worked.

- Add all your files to the “staging area” using the command: git add -A

- Use the command git status and verify that all of your files have been moved to the staging area of git.

- Commit all your files to the repository using the command: git commit -m”initial commit”

- Use the command git status and verify that all your files are now in the repository. (The repo now exists on the local drive. The next steps create the remote version on GitHub and make a public version of it that can be viewed online.)

- Go to github.com, log in, click the ‘+’ in the top right to create a new repository.

- Give this repository the same name as your local repository.

- Click Create repository. Do NOT initialize with a README file or add .gitignore or a license.

- Connect your local repository to your remote repository: (“Local” just means the repository on your computer and “remote” means the repository saved on GitHub.) To connect these two from local to remote, follow the directions on the web browser screen (the ones that appear after you created the repo) and type: **git remote add origin url_from_github. (This url is located in the browser next to [quick setup].)

- Back on your computer, use the command line to have git send the work from your local to the remote: Type git push origin master.

- Refresh the browser and you should see a page listing the files that you have in your local repository.

- Make sure the local and remote branches match.

- Create a new branch called “gh-pages” on GitHub. This will magically create a web server for you. It can take up to an hour.

- View the settings on your repository to see at what URL your files have been published. It should have the format: yourUserName.github.io/yourRepoName

- View your web site at the URL.

Here’s how it works if you start on GitHub:

- On GitHub, create a new repository. You may want to initialize the repo with a README.md file.

- Clone the repo using ssh to your local machine using the command: git clone git@github.com:YourRepoName. (This info will be provided as soon as you create the GitHub repo.) DO NOT USE THE “CLONE TO DESKTOP” BUTTON.

- Go inside your new local repo (on your computer) with the command **cd YourRepoName

- BACK ON GITHUB: Make a gh-pages branch. Click on the Branch dropdown menu, and make a new branch called gh-pages. (This is a special branch, because it’s automatically public.)

- Once there’s a gh-pages branch on GitHub, move it to the local repo, by typing git fetch origin gh-pages.

- To move between branches, use the git checkout command, and specify which branch you want to move to: git checkout master (to move to the master branch) or git checkout gh-pages (to move to the gh-pages branch). Once you’ve created the new gh-pages branch, move into it to wake it up so that git will see it.

- The command git branch will show which branch you’re working in. The one that’s active will have an asterisk next to it (and may be green, depending on your Terminal is set up). git status will also show the active branch.

- Move back into the master branch (git checkout master), and do all your work in the master branch until you’re ready to publish on the gh-pages branch:

- master - Where you do your work.

- gh-pages - Where you deploy your work so that it can be seen publicly.

- For collaborations, you may have a third branch, to do work that you will later add to the team effort.

For this next project, we’re going to use HTML5 Boilerplate. It includes a lot of things that you’d find in a production website, such as an index.html file, folders for CSS and JavaScript, a robots.txt file, etc. The challenge is reading and understanding code made by someone else.

Once the boilerplate files are in place:

- git add -A - This is a good place to use this command, because there are so many new files and directories.

- **git commit -m”Initial commit”

- Once the commit is done, the local repo will be ahead of the remote by one version. To update the one online: git push

- Now, to publish the changes, they have to be moved to the gh-pages branch. First, move to the gh-pages branch on your computer: git checkout gh-pages

- Next, you need to move the changes that have been made on the master branch into the gh-pages branch. This is done with the command git merge master. (The branch that needs the changes calls to the other one – so in this case we’re in the gh-pages, and making the request to the master branch.)

- Once the gh-pages branch has been updated, push it to the remote version online: git push

When in the Terminal, you can open the the current command-line directory in the Finder by typing open .

- git status - Shows you what’s been going on with git add and git commit. Lets you inspect the working directory and the staging area.

- git log - Displays committed snapshots. It lets you list the project history, filter it, and search for specific changes. Unlike git status, git log only operates on the committed history.

- git branch -va - Shows the state of all brances and versions. (a shows all, v shows the latest)

To make git ignore a file, create a .gitignore that lists everything that shouldn’t be adding to the staging area or committed: touch .gitignore

To remove a repo: rm -rf .git

Agile stand-ups: Try to do your stand-up in three sentences, one for each question. (Teaches techniques useful in elevator pitches.)

When learning a new software, always go through all the menu bars, because those advertise all the functions.

We’ll do a big exercise with Chrome Developer Tools later, but for how, here are three ways to access them:

- Command + Option + I

- View > Developer > Developer Tools

- Drop-down menu at the top right of the browser window

This will open the most complicated browser interface we will encounter. To keep things simple, there are four controls we need for now:

- The Elements pane – Shows the DOM (Document Object Model, which is the browser’s interpretation of the site), not the HTML.

- The Styles/Properties pane – Styles shows the CSS (including which styles are being applied to a particular element); Properties shows everything about the element.

- The Dock Side buttons, which control where the Tools appear in our window.

- The Close button, to make it all go away.

Styles shows how styles are being merged to create the look of the page. We can use this to analyze our pages.

View > Developer > View Source – Shows the actual code for the page. View > Developer > Developer Tools – Shows the browser’s use of the code.

There’s always a reason why something happens on the page, and the gibberish in the Developer Tools will make and more sense, the more we read it.

“User Agent Stylesheet” refers to styles that we didn’t write. Browsers have built-in styles (in case the developer doesn’t write something; this can be overruled as part of our styling.)

More: Great Hidden Features in the Chrome Developer Tools

#####The Cascade

There are three ways to assign styles:

- Inline style attribute (inside the HTML tag) – NOT GOOD! Means you have to laboriously change every instance of that attribute to change the style.

- Internal style sheet - In the head element of the HTML.

- External style sheet, which the HTML refers to via the link element (also in the head element)

CSS stands for “cascading style sheet,” and there are three factors that affect which CSS rules are used for a particular element:

- Proximity – The closer the style is, the more priority it has. (The order, from highest to lowest priority: inline, internal, external)

- Specificity (e.g. ID is more specific than a class, a class is more specific than an element)

- Inheritance - If you don’t specify a style the child will inhereit from its parent container.

In our class, no reason to use anything but proximity and specifity, plus external style sheets.

Use Chrome Developer Tools to analyze where the styles are coming from. (In Dev Tools, you can turn on “Show Inherited)

Can experiment in Codepen, to see the cascade in action and see which selectors take precedence over others: Cascade Demo.

#####CSS Positioning and Floats

HTML’s primary job is structure. We now all practice semantic markup. We can define our own tags (and often do in Angular).

Developers were using many class names over and over. In HTML5, those common classes have become new semantic markup. For example, what would have been:

<div class="nav"></div>

is now:

<nav></nav>

Other new tags in HTML5 include:

- header - Material at the beginning of a section or page

- footer - Material at the end of a section or page

- main - Main content of the page

- article - Redistributable chunk of content, that can be seen on website, or Facebook, RSS (real simple syndication), Flipboard (a newsreader with curated content and a very intuitive interface).

- section - Part of a page

- aside - Sidebars

- nav - Menus

(Fonts: Font Squirrel. Can use own fonts, package them.)

Some basic structural setup:

- Analyze work, going from the top of the page down.

- There can be only one body element on a page. (May also put all the content on the page into another container INSIDE of the body; you can’t apply margins, especially negative margins, to the body element.)

- Put the nav element first, so that it’ll be first on small devices.

Ask yourself, how am I going to structure the code?

- For the next developer?

- For search engine robots?

- For the user?

The h1 element is very important for telling Google what’s most important on the page. The rule used to be only one h1 per page, describing the main content of the page. Now, in HTML5, it’s not only possible but recommended to have more than one h1 on a page. More info on that here. (A div, like section and article, is a block element, as opposed to an inline element.)

A basic page structure might be:

<body>

<html>

<head></head>

<body>

<main>

<h1></h1>

<nav></nav>

<section>

<article>

<header></header>

<h1></h1>

<h2></h2>

<h3></h3>

<p></p>

<footer></footer>

</article>

</section>

</main>

</body>

</html>

</body>

At this point, we don’t care about the content; we care about the type of content.

Example of a very nice responsive site: Cool Hunting.

A very important resource for us is caniuse.com, which keeps track of which new features are supported by browsers (and which work-arounds we might have to use). There are some newer things that are not supported enough to use, such as the new picture tag.

As web developers, we’re on the publishing end, always pushing out new content.

You can always trust the new versions of Chrome. iOS Safari uses the same engine that runs Chrome.

In CSS, you use selectors to choose which parts of the HTML you’re going to apply the styles to:

- Elements are just listed by name (h1, p, nav, etc.)

- Classes are preceded by a .

- ID’s are preceded by a # (Typically, people are getting away from the use of IDs.)

(Those are the three kids of selectors we know so far; there are many others.)

#####Floats

There are a couple of different positioning mechanisms.

When using a browser, you’re looking at a window. As you define things in HTML, if you don’t give specific instructions, it will start packing things in a certain way. By default, block elements are stacked on top of one another. The browser reads the HTML from top to bottom, and each block element takes up the full width of the page. Whatever is next, goes below it on the page. Each box bubbles up from bottom to the top.

To make them appear side by side, you can use the float CSS rule, as in this Codepen Demo.

(Though the classes in this pen are named for their appearance, don’t do that in general: name them for their function or meaning: navbar, quote, etc.)

float: left has to be there for all three boxes, to make them appear in a horizontal line. You have to control float on all the elements take total ownership.

When you float (as in this case), float all the elements to the left.

- position: static; - Normal Behavior.

- position: relative; - Positions element relative to where it would have been normally and leaves a gap where it would have been.

- position: absolute; - Positions the element relative to its container. (Good for a nav bar)

- position: fixed; - Position is constrained to a particular place on the viewport and won’t respond to scrolling. (0, 0) for the (x, y) coordinates is at the TOP LEFT of the screen.

- position: sticky; - Not well supported, and probably won’t be. Keep checking, but don’t use it yet.

- Details on the position property

Beware of “cargo cult” coding: it’s easy to borrow other people’s code, and in doing so, to include code that you don’t understand. You’re not being honest with yourself, because you’re not really coding. It can be part of the learning process, though: at first you may do things that you don’t understand (cargo-cult style), then you’ll follow (and understand) recipes – and that will lead to mastery.

Front end Template: HTML5 Boilerplate